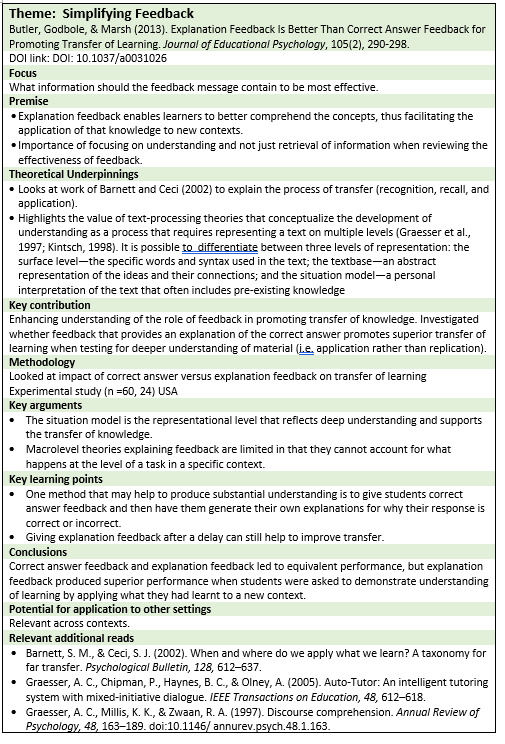

5.4 Developing Metacognitive Competence

Feedback is viewed as central to the enhancement of the learning process (Hawe & Dixon, 2017), and the development of self-regulated learning (Fyfe & Rittle-Johnson, 2016). Hattie and Timperley (2007) discussed the power of feedback to impact learning when it is focused on supporting students in how to improve their work.

DeNisi and Kluger (2000) highlighted the negative impact of feedback when it did not have potential to impact outcomes (i.e. looking back rather than supporting moving forward). Sadler (2010, 2017) has bemoaned the amount of time spent contemplating feedback when efforts should be placed on supporting students to immerse themselves in situations where they are able to calibrate quality for themselves through carefully guided exercises such as marking and moderation of work.

Evans (2016, 2020a,b) in agreement with Sadler (2010) highlights the importance of broader interpretations of feedback to include students’ self-feedback and feedback seeking and using skills. She argues that given the vast number of variables impacting student receipt and use of feedback, assuming feedback is ‘good’ in the first place, efforts should be placed on designing integrated learning experiences which give students progressive opportunities to experience what quality looks like and how to achieve it. Key messages from the literature regarding self-regulation of feedback include:

Feedback as a learning process with the learner as central to it

‘‘feedback must be conceptualised as a supported sequential process, rather than a series of unrelated events’’ (Archer, 2010, p. 106).

The need to move away from a receipt model of feedback to encourage student ownership and direction of the feedback process through ensuring transparency of the assessment process, and student access to requisite information to enable them to make informed decisions (Evans, 2013).

“Feedback should not be about the delivery or receipt of information at all. Instead, it should be about identifying appropriate challenges (i.e., desirable difficulties) that enable individuals to maintain their perspective as competent and conscientious practitioners while also continually evolving their practice” (Eva & Regehr, 2013, p. 464).

The learner needs to be a central agent in the assessment and feedback process, and therefore aware of criteria of success, and their role in developing competency in self-assessment (Boud, 2015).

Efforts should be on supporting students to build capacity to seek, interpret and use feedback rather than focus all efforts on providing expert feedback (Du Toit, 2012; Nicol, 2009).

More attention needs to be placed on the mechanisms and procedures of implementing formative feedback strategies to enhance self-regulation (Bose & Rengel, 2009).

‘The most direct approach to evaluating and improving the effectiveness of feedback is… for teachers to audit their students’ subsequent work themselves, and to adjust their feedback in response to the results’ (O’Donovan, 2014, p. 1028).

Supporting students to make sense of feedback

Clarity of message

Dominant disciplinary discourses need to be made explicit (Van Heerden et al., 2017) and students need to be encouraged to articulate their tacit knowledge (e.g., existing motives, ideas, opinions, beliefs, and knowledgeable skills) (Clark, 2012).

Given individual differences in learning, the feedback message needs to be kept simple and focused on what matters most.

Facilitating dialogue

Feedback needs to be dialogic to support student self-regulation, efforts should be placed on those interactional features that promote and sustain feedback dialogue (Ajjawi & Boud, 2017; Al’ Adawi, 2021; Yang & Carless, 2013; Evans, 2013).

Feedback should be based on well-defined, negotiated goals rather than purely on the quality of the learner’s performance given the numerous goals (specified and unspecified) in play and impacting student decisions (Eva & Regehr, 2013).

People are unlikely to change in response to data-delivery methods that attack their self-perceptions’ (Eva & Regehr, 2013, p. 463).

Efforts should be placed on checking students’ interpretation and use of feedback: does feedback achieve what we need it to?

Preparing for feedback

Students need to prepare for feedback. Where students have insufficient knowledge, detailed feedback may be inappropriate as students may not be able to process this. Similarly sufficient time is needed for students to process feedback messages prior to discussions about how to move work forwards; this introduces the notion of space to process feedback to maximise effectiveness of feedback encounters with others.

Opportunities to construct own meaning

Students must have opportunities to construct their own meaning from the received message (Clark, 2012; du Toit, 2012; Sadler, 1989).

If students are to learn from feedback, they must have opportunities to do something with it (Nicol, 2010; Carless et al., 2011; Price et al., 2011).

Students need multiple opportunities to assess work for themselves so they can internalise the requirements of assessment (Sadler, 2009b).

ACTIVITIES

1. Review the distribution of assessment tasks on your module to see if feedback is positioned appropriately to enable students to make best use it to inform the quality of their work.

2. How can you streamline feedback to maximise its effectiveness (focusing on the key message?

3. What activities are in place to check students’ understanding and use of feedback?

4. What opportunities do students have to mark and moderate work?